01

THE MUSEUM

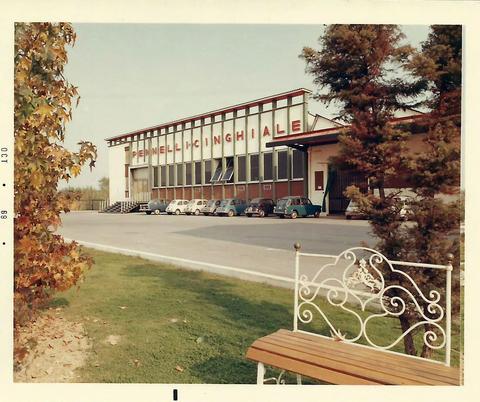

Let us begin the story of the paintbrush in the last chapter, in the Pennelli Cinghiale Museum of Time.

Here, past and present are inextricably linked: the museum takes you on a journey through time, bringing together documents from the archive, testimonies, rare examples of industrial artefacts, awards (the latest - although by no means the least important - is the title of Historic Brand of National Interest), as well as multi-media and multi-sensory content.

And the key word that crops up again and again in the stories and experiences of company founder Alfredo Boldrini is contemporaneity: that impalpable yet extremely concrete sense of a world in evolution, of sensibilities that are constantly changing. This is the formula that has given rise to a “Love Brand”, which, according to certain marketing theories that emerged in the early 2000s, is a brand with the capacity to create a unique relationship with the consumer, a relationship in which customer loyalty - and indeed love - goes far beyond rational choices.

In light of all the above, it was only natural to entrust this museum-in-the-making, destined to showcase the brand’s past, present and future, to a contemporary artist who has used his creativity to transform a simple tool like a paintbrush into a ready-made museum piece.

DutyGorn is the artist whose works adorn the spaces in the museum.

The link between his art and the company that created the “Great Brush” needs little explanation: anyone who comes into Cinghiale, immediately appreciates the importance, complexity and originality of his work. As well as how Fate enjoys creating winning formulas, by combining sources of inspiration with stories from a distant past. Along with the installation that introduces the Museum of Time, the artist produced a number of works, making many of them available to the museum and creating a highly original timeline. Accordingly, there is a seamless link between the artist’s work, which reveals the founder’s path, step by step, and the paintbrush. The museum unveils its highly relevant legacy showcasing both the manufacturing side and the founder’s vision.

02

THE TECHNOLOGIES

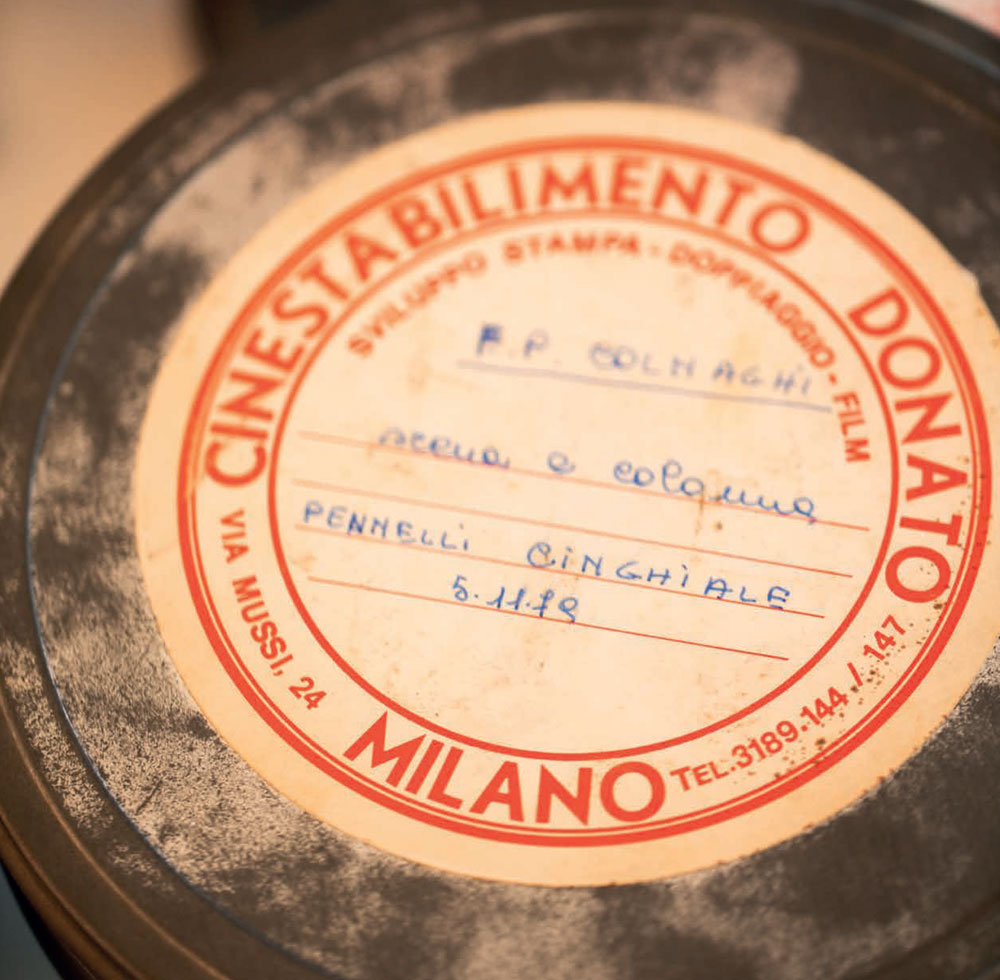

A Bakelite wall telephone, two machine tools from the 1950s and 1960s, pizza-shaped film reels, wooden crates with Chinese writing lost in the mists of time and space, as well as memorabilia in the form of paintbrushes in their original packaging: in the Museum of Time, these rare pieces are an integral part of the jigsaw puzzle representing the long history of Cinghiale.

There are a number of these in the first room (including a telephone that hides a neat little technological trick: on lifting the receiver, visitors can listen to an introduction to the tour), along with others scattered around the entrance and in the hall. They bear witness to the ongoing relationship between the company, the most innovative technologies and the least explored markets. From the very beginning, innovation has been at the heart of everything the company does.

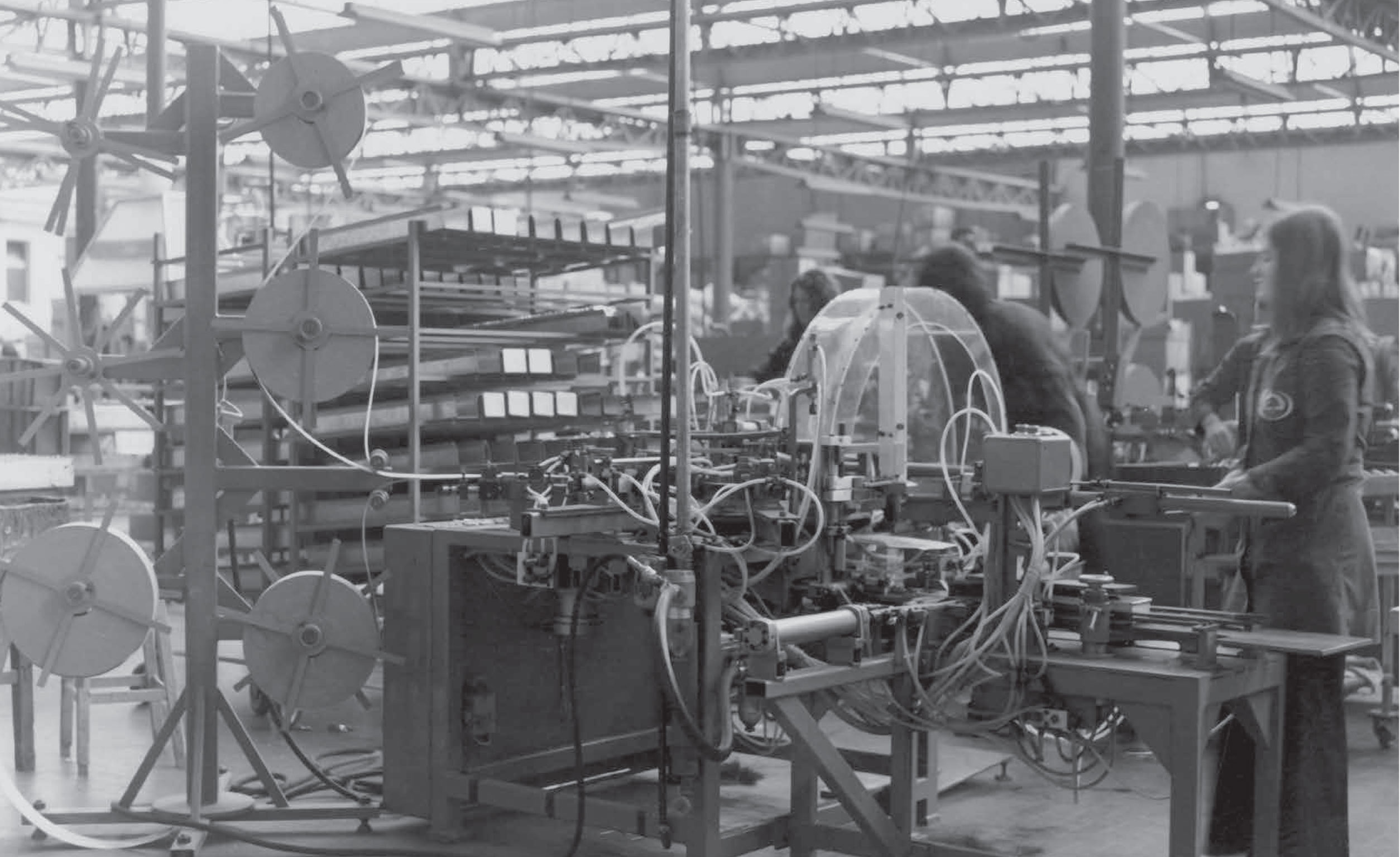

Examples of this are a hooking machine from the late 1950s, and a vibrating machine from a few years later. The first piece of equipment museum visitors come across tells the story of the company, projecting images and videos of people and events that its “memory” has recorded.

Bristles from China were another novel product for a sector accustomed to sourcing its raw materials from the domestic market.

From the 1970s onwards, the constant use of advertising at sporting events, as well as on the radio and television (as evidenced by the old film reels found on the company’s premises and restored by the Cineteca di Bologna) caught many entrepreneurs of the time off guard.

1980, the year that saw the advent of computers in the company. “From one day to the next, we were told: throw away your pens, from now on we’ll only be working on computers” recalls Leda Coazzoli, a former employee.

The Cicognara factory champions sustainability through a series of concrete procedures: production is powered by certified wind energy, the plastic used to make paint buckets is recycled and recyclable, the wood of the paintbrush handles is FSC® certified and comes from sustainably-managed forests, and the chemical formula of the bicarbonate of soda paint contains 95% green ingredients.

At the same time, technological advances continue apace: the most recent example of this is the new Industry 4.0 robotic plant for fullcycle production of 11,000 flat paintbrushes per day.

Technology is also crucial for sales and marketing: the new Cinghiale showroom features an integrated high-definition camera system, designed to enable customers to connect from anywhere in the world, in order to select a new product, having examined every last detail “live”.

03

THE ACCOUNTANT

The lengthy conversation with Sergio Parazzi, recorded while the Museum of Time was being prepared, represents an authentic professional and personal legacy.

“The Accountant”, as he was known to everyone in the company, was born in 1927, and passed away in June 2021 at the age of 94. He joined the brush factory in 1955 and worked there for 33 years, quickly becoming Alfredo Boldrini’s right-hand man: «We always used the formal form of address when speaking to each other, right up until his death», Parazzi said of Boldrini in the interview - a mine of information about the company, its founder and Parazzi himself.

Let’s begin with him, then. He came from a large family, and for this reason, was destined to continue his education after primary school at the technical college in Castellucchio. However, one of his teachers (a Ms Margonzi, from Mantua) objected, insisting: «This boy must study». So little Sergio completed middle school and went on to qualify in accountancy. Then came the war, prison, and a series of temporary jobs. Until he met «Signor Alfredo», who was insistent that he join his company: «He would come to my house in the evening before I got home from work, so that he could talk to me and try to persuade me to join». Boldrini eventually succeeded, and a close professional relationship developed between the two men.

Parazzi was there through every stage of the company’s development: from the very beginning, when it only employed six people, up until the number of employees grew to 170. «Right from the start, we made sure that everything was in order from a legal standpoint, and we were seen as mad for doing everything by the book». The Accountant contributed to the technological development of Cinghiale, introducing first machinery, and later computers (back in 1980).

Together with the Commendatore, they broke free from the shackles of local banks and found financial backers in the credit institutions that supported the national economic boom. His memories of Boldrini are respectful, affectionate and full of anecdotes: «Family and friends always called him Pierino, but for me he was always Alfredo». For years, or rather decades, they sat at desks facing each other: «We sometimes had heated discussions, but we never fell out. Boldrini followed the entire production process closely; he was a true expert when it came to paintbrushes and he only had to hold them in his hand to understand their characteristics, merits and flaws. And to decide on the price». And, Parazzi adds: «He would never leave a customer without first having agreed on a sale. He was a very persuasive person». The Accountant was the person who was responsible for creating the “Great Brush” of the famous commercial, and bore witness to

the huge success enjoyed by the company. When he finally left the company, he turned his attention to politics for a time, becoming mayor of Viadana from ‘93 to ‘97.

The last of his memories concerns his mentor: «Boldrini was very intelligent; he immediately had the measure of the people he met, and he was also a very generous person. He was a man you wouldn’t forget, a man who stayed in people’s minds».

04

THE WOMEN WORKERS

Sometimes the stories of someone who was there, and their recollections of everyday life, can describe a certain era so much better than a sepiatoned photo album ever could.

Luisa Passerini and Marisa Bertoli, now both in their eighties, were part of the Pennelli Cinghiale adventure right from the start. Their memories remain vivid and reliable, despite the passage of time. Both worked for the company as manual workers, first in the old factory and then in the new one. Another thing they have in common is the fact that they met their husbands there, and worked side by side in the Cicognara warehouses. And the third thing they had in common - they achieved their lifelong dreams of buying their own houses, thanks to the support of Boldrini and the management.

Luisa remembers exactly when she joined the company - it was in 1953. For her, Cinghiale initially represented a place of social liberation for her and a place that enabled her and her family to become financially independent. «When there was an inventory to be done, we would immediately volunteer because we were paid overtime. We worked so hard, hand-tying the bristle tufts for the paintbrushes. But we liked doing it because we needed the work». And when they started thinking about buying a house, it was Signor Boldrini who provided them with the money for the deposit. And she has fondly held on to the medal that the company gave her when she retired.

Marisa also started working at the factory in the 1950s, and stayed there until she retired. Her job enabled her to be financially independent, something that meant a great deal to her, and something that was important to her even after she married. Her husband also worked at the factory, and that is where they met. She immediately made her position clear to him: «Look, I’m going to carry on working, because I don’t want to be dependent on anyone». It is no coincidence that she herself recounts that, before the Christmas holidays, when they came out of the gates of the Cinghiale factory and bumped into the girls from other factories in the area, these girls would make fun of her and her co-workers: «They gave us a panettone. Didn’t they give you anything?» And Marisa would reply: «They gave us a bonus of an extra month’s pay, which is much better than a panettone!»

An answer worth more than a treatise on welfare!

05

THE SHAREHOLDER

"The art of selling"

This chapter of the history of Pennelli Cinghiale could also be entitled: “The art of selling”. The Mantua-based company has always relied heavily on its “ambassadors”, its sales representatives in every corner of Italy.

Pietro Rivoletti was one of them. He has the look and manners of a gentleman from another time, and he looks younger than his 84 years; his memory would make many a young man jealous. His manners are calm, as is the tone of his voice, in which there is a hint of a Bolognese accent. He learned the art of selling directly from Boldrini himself. Indeed, Boldrini followed him closely when he started out and was responsible for training him, as he was in turn for many other representatives.

The pupil admits that he never surpassed the master («Boldrini was unbeatable»), but that he did well, thanks in part to the advice he received: «He told me that when meeting our customers, I had to act as if I was a shareholder of the company I worked for, not just a sales representative. I was young, and I felt proud that he had placed so much trust in me».

The rest came naturally: with his briefcase full of samples, Signor Pietro travelled the length and breadth of the Emilia Romagna region, and was a constant presence at the major trade fairs which the company took part in, such as the International Building Fair in Bologna (SAIE). Eventually, he would become the doyen of the sales reps, and a reference point for everyone. He has now passed the baton to his son, who is following in his father’s footsteps.

06

THE FOUNDER

«A young man with little money and lots of dreams»: this is probably the best description of the young Alfredo Boldrini. This was how he was described by the person who knew him best, the love of his life - Valeria, his wife.

The childhood and youth of the founder of Pennelli Cinghiale has been written and spoken about at length. As in a famous novel, his personal and professional journey can be pieced together from the fragments of the memories of those who met him, those who loved him, those who admired him and even those who envied him.

This biography made up of many different voices begins when Alfredo, born in 1920, began to work for a living at the age of only seven. The horse-drawn cart that would set off towards the south from Cicognara is something that many of Boldrini’s friends and relatives can clearly remember. There are those who recall that, after leaving the impoverished countryside where the main crop was broomcorn, he would arrive in Parma or the Apuan Alps and, together with his father and brother, would stop in church squares on Sundays to sell his cargo of brooms. «And they would not come back until all the brooms had been sold». It was a very humble trade, but it provided him with invaluable experience. After finishing primary school, he continued to work here and there as he could. Then, he was called up into the army. Boldrini ended up in Turin, but according to other people he didn’t spend his free time chasing girls. Instead, he rented a space, filled it with products (still brooms at this stage), and sold them to the housewives of Piedmont. When he returned to Cicognara after the war, the paintbrush and broom market was in its infancy, and Boldrini was one of the first to throw himself into the sector he knew best brooms.

The first people to work for him in his factory were five women workers and an accountant who was a refugee from Dalmatia.

This may seem like a very small workforce, but in the decades to come they would achieve one milestone after another for the Mantua-based company. The owner was the archetypical self-made man of the era, from the Po valley. Despite his success and wealth, he always made a point of getting to know his employees personally, taking the trouble to find out about their needs and concerns, and he was always ready to teach

his representatives the art he knew best - that is, the art of selling. His instinct was one of his defining characteristics, and one which features prominently in all the stories about him.

He was fixated on finding distant, unexplored markets. And it was this instinct that led him to go as far as China to find the valuable raw materials he needed for the paintbrushes. His ties with Maoist China can be seen in Cinghiale’s archives, and in the remaining crates that once contained the bristles. It is no coincidence that the Republic of China established diplomatic relations with Italy, Alfredo Boldrini was one of the few Italian industrialists invited to the opening of Beijing’s embassy in Rome. Something Boldrini would

always be extremely proud of. Meanwhile, in Cicognara, everything had changed. From the 1970s, it became known as the “town of billionaires” (a phrase originally

coined by an article in L’Espresso in 1971). Statistically, the village where paintbrush and

broom factories were proliferating had the same number of cars per capita as the United States. A documentary buried in the RAI archives (an old “TV7”) shows the outlandish architecture of several of the villas built by its newly-rich inhabitants. Boldrini built himself a house too (with clean lines, nothing fancy), within walking distance of the factory. In the village, he stood out due to the fact that he always wore a jacket and tie - and a Borsalino hat, naturally - and in the summer, a light-coloured suit (Boldrini was convinced that clothes make the man, so he would buy his representatives a smart suit in which to go and meet their customers). His cars were pretty impressive, too: an Ivorycoloured Jaguar, a flaming-red Lancia Aurelia and other stunners. His passions included food («He liked to eat well, perhaps to make up for the hardships of his youth») and the Inter and Mantova football teams. He was a regular visitor to the barber - the latter saw to his needs for decades, and Boldrini would give him a few good stock market tips from time to time. The

rest was work, work and more work, which he shared with his wife Valeria.

SO MUCH MORE THAN A WIFE

A “family” business can be many things. In the case of Pennelli Cinghiale, the history of the company wouldn’t have been the same without the involvement of Valeria Madesani Boldrini. Born in 1922, she was the daughter of a River Po fisherman, and as a little girl she lived in a house near the river. She was tall and slim, with slightly Asian features. She would tell her family that Alfredo would come and call out to her at night from under her window, trying not to be heard by her parents. One night, during one of their secret meetings, he said to her «Here, this is for you», and handed her something that was rather poorly wrapped in a piece of paper. In the moonlight, she could see that it was a small gold watch. She would have many more, including some valuable ones, later on, but this was the only one she would ever wear.

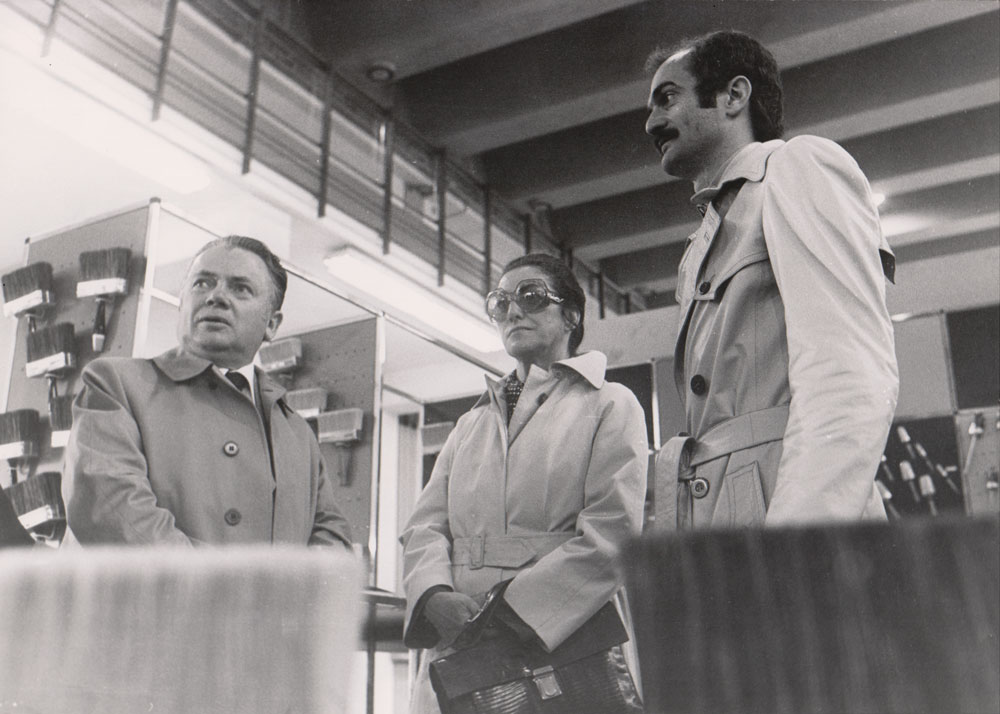

Valeria was a strong-willed, feisty woman. She was highly respected and somewhat feared by the women who worked at the factory, although she did bring them 5 o’clock tea every day, and confidently supervised maids, housekeepers, nannies and gardeners. And she always stood her ground with her husband. While Alfredo was away on business, she secretly took her drivers’ licence examination. He did not want her to drive, and was very upset when he returned: at that time, women didn’t generally drive, and Valeria was

one of the first to do so. She eventually won the battle, and Valeria would often drive over to Cremona in her Alfa Spider. She always boasted that she had the same seamstress as the singer Mina.

She was always very elegant, often wearing long dresses. Valeria played an important role in the success of the company. A short description by a family member describes her better than a thousand words: «She was by no means a typical grandmother», explain her granddaughters, «She was more like the Queen of Egypt».

07

RECOGNITION

Pennelli Cinghiale has won multiple awards throughout its long existence. The Museum of Time has dedicated a space to these - an important chapter in the history of the

company.

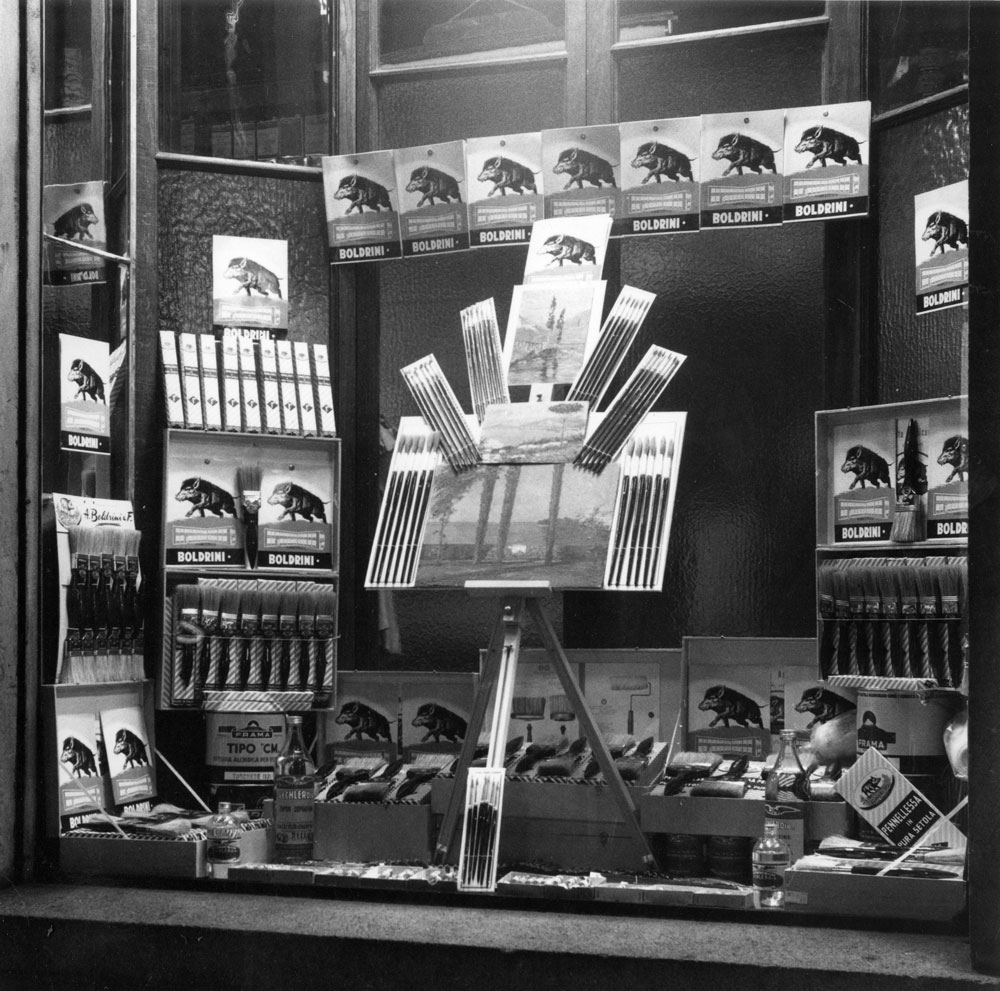

In times gone by, when the market operated very differently, official awards could have a significant impact on the image of a company and, for this reason, Alfredo Boldrini was justifiably proud of his company’s various accolades. Companies would use them as a marketing tool by putting them in pride of place in their catalogues, on their letterheads and in all their official business communications with their customers.

The company received a host of coveted awards, including the Ambrogino d’Oro in 1971, the Europa Mec in 1972 and the Mercurio d’Oro for the first time in 1974. The Premio Qualità Italia deserves a special mention: awarded as a result of surveys conducted directly with consumers, it is worth more since it represents the view of the general public. For Cavaliere Boldrini - who would later become Commendatore Boldrini - this was the award that he valued the most.

Incidentally, for a man like him, obtaining recognition from Italy for his achievements (the title “Cavaliere” was bestowed upon him in 1959, and “Commendatore” in 1977), was more important than a couple of university degrees. Today, the success of a company is measured in many different ways, but for Pennelliì Cinghiale, the awards keep coming.

In 2021, the brand from Cicognara was added to the list of Historic Brands of National Interest by the Ministry of Economic Development. Created in 2020, this is a listì containing a small number of Italy’s most iconic brands, including Benetton, Cirio, Amarena Fabbri, Poltrona Frau, Illy, Sergio Rossi and many other market leaders in their sectors.

Today, the fate of Cinghiale is in the capable hands of a strong all-female team consisting of Alfredo Boldrini’s granddaughters: Eleonora Calavalle, CEO and Clio Calavalle, as well as their mother Catuscia Boldrini, who is company President.

08

NOT A BIG BRUSH, BUT A GREAT BRUSH

The word “iconic” has often been used to describe the “Great Brush” commercial, in which the painter pedals through the Milan traffic. And it’s no exaggeration. That explosive exchange («You don’t need a big brush, just a great brush») has stood the testof time. Ignazio Colnaghi first came up with it at the factory in Cicognara, one day in 1982 that many still remember because he shouted at the top of his voice: “We’ve got it!”.

Colnaghi had long been one of the best brains in television advertising, which, at that point in time, was still an emerging sector in Italy. An actor from the Piccolo Teatro, dubbing artist and commercial writer for Carosello, the Milanese creative artist had invented and given voice to the famous Calimero Pulcino Nero twenty years previously, who was known for his two catchphrases: «Ava come lava» (Ava, how well it cleans) and «È un’ingiustizia però» (But it’s not fair!), phrases that struck a real chord with the Italian public.

The success of the “Cinghiale” commercial, then, was not down to chance or luck - rather, it was the result of a strategic decision by Boldrini, who always made wise investments, and had absolute faith in the power of television as a marketing tool. Marketing experts have analysed what was so innovative about that short commercial, and have identified its quality, functionality and vision: the viewers enjoy watching the protagonists as they move through real traffic, and the pun stems from the fact that in Italian, the change in position of the adjective («pennello grande, grande pennello») (big paintbrush, great paintbrush) changes the meaning of the phrase, emphasising quality over size; the characters of the policeman and the painter are taken directly from everyday life, and despite a scene that could easily be described as surreal due to the presence of that giant paintbrush, they are immediately recognisable.

The commercial has pride of place in the company’s Museum of Time. But on digging deeper into the past, as we look through the documents and materials held at Cicognara, we realise that this was the culmination of a journey that began much earlier. Boldrini believed in advertising and corporate image, making him a pioneer among other

industrialists of small or mediumsized companies.

Let’s start with the boar symbol which, as their staff know, actually has very little to do with the direct production of paintbrushes. Yet it is a highly evocative name!

Soon after, TV arrived on the scene. In the Cinghiale films restored by the L’Immagine Ritrovata photo laboratory, perhaps the best of its kind in Europe, with links to the Cineteca di Bologna, we see the footage of 1970s commercials featuring elegant wives and hardworking husbands with innocent, happy children, and then, in 1981, the great Milanese actor Piero Mazzarella.

The arrival of the “Great Brush” commercial saw the brand take off all over Italy. And its influence is still being felt today. For example, once the actor and model Francesco Papi, who played the policeman, went back to the Piazza Castello where the commercial was shot, dressed in uniform and holding a paintbrush. Many recognised the character, including a young couple who weren’t even born when the commercial came out!

09

SPORTING PASSION

Alfredo Boldrini has always understood the importance of advertising at sports events because of their great appeal to the general public.

Once his company had reached a certain size, he chose to advertise in the following ways: sponsoring cycling teams and automobile races, as well as stadium advertising, thanks to his relationship with Sandro Mazzola, one of his sporting idols, who at that time was still playing for Inter Milan, the team closest to his heart.

10

THE ARTIST

Duty Gorn was born in Milan, the city where he currently lives and works. He works not only on canvas, but also using threedimensional media, murals and performance art, creating art that is immediately recognisable, dynamic and clearly defined, in terms of both his style and the subjects he portrays.

His works are exhibited in art galleries and public buildings.

Polyeclectic

Acrylic on wall - 2022

The lines of this piece are designed to distort time, creating a sense of dejà-vu, the future feels familiar to us as it turns back towards the past, a play on time that disrupts the space-time continuum.

Upside down

Installation - 2022

The aim is to draw the viewer into the work, provoking an emotional response and triggering memories associated with the colours. As the artist himself explains: “The project is the result of meticulous researchand a profound aesthetic sense of the reinterpretation of the materials, and the way these are used and re-used”. The paintbrushes used for the Museum installation were transformed into a new artistic form, breathing new life into them.

Retouché

Markers on glass 60x80 cm - 2022

The black-and-white images trace the historic link between Pennelli Cinghiale and sport. The work reinterprets these images with a futuristic slant, with strokes of marker pen evoking a past that is still present today.

Brushes over time

Acrylic on layered canvases 159x162 cm - 2022

Acrylic on layered canvases 159x162 cm - 2022. This collection of works signals a change, a process of evolution that begins in the past. This gives rise to a visual chronology interspersed with a series of lines, which, like the hands of a clock, mark the passing of time. A view spanning both past and future.

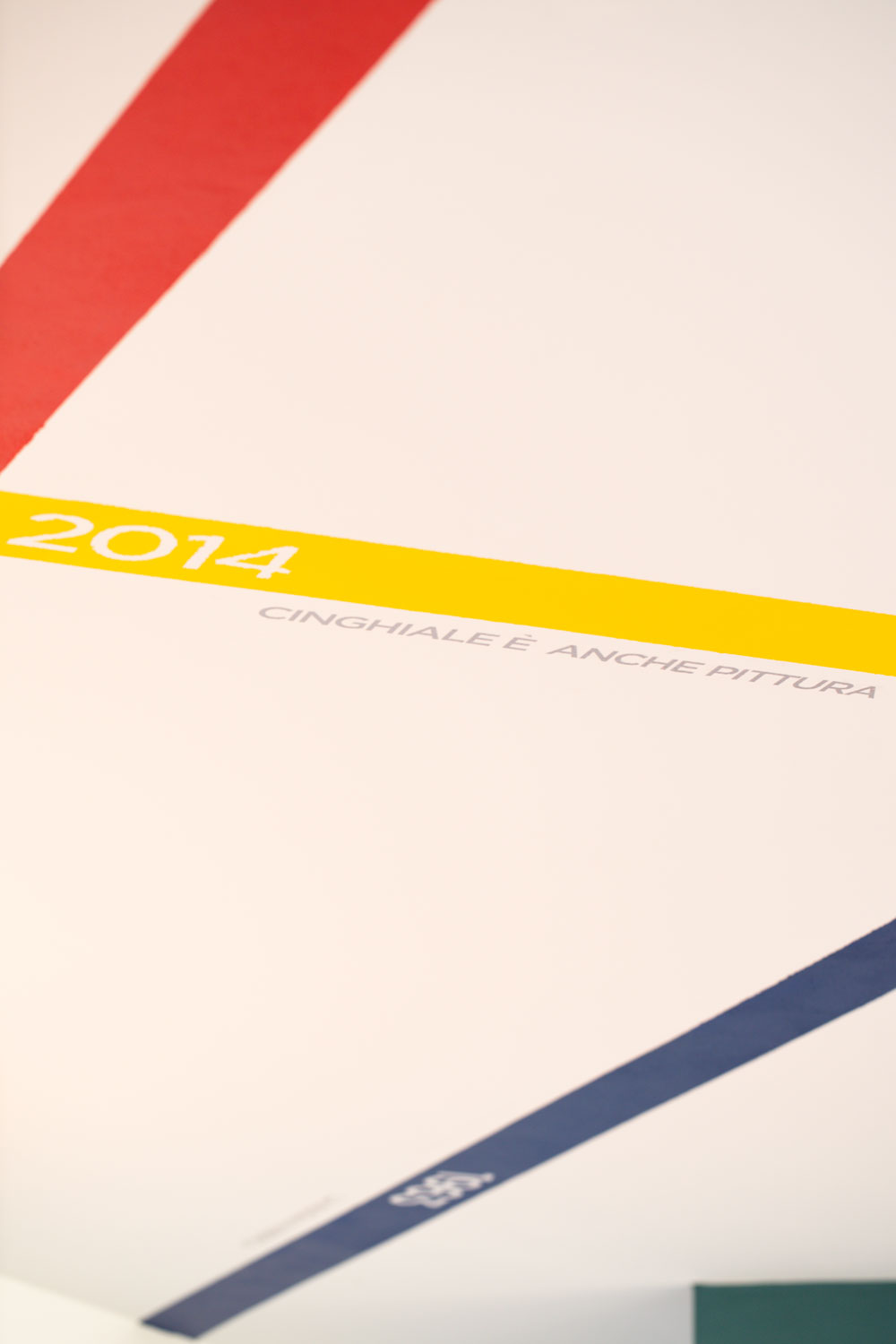

Abstraction

Acrylic, spray paints and markers on layered canvasses 455x150 cm - 2014

A timeline of acrylic geology. This is what the faces in this work, which are interrupted by movements, represent. The work breaks up, transforming itself into something different, fragment after fragment. Each change has its own colour identity, which allows the observer to formulate his orher own subjective interpretation of the piece.

The mural

The mural, entitled “Time Mirror”, covers the façade of the Pennelli Cinghiale factory in Cicognara. It can be seen from Via Milano 222, and was created using only Cinghiale paints, paintbrushes and rollers.

A set of colourful lines and a woman’s face - two elements that have always marked out DutyGorn’s work.

The brush strokes and style are reminiscent of graffiti art as well as other notable movements in 20th century art, particularly Pop Art.

The lines also call to mind those found in the works that DutyGorn has created inside the Pennelli Cinghiale building, thus forming a pathway connecting the interior with the exterior: they are designed to create a distortion in time, a sense of dejà-vu, in which the future feels familiar to us as it turns back towards the past, a play on time that disrupts the space-time continuum. Colourful lines cut across the surface and criss cross like rays of light, unfurling across the space and going beyond the edges, in theory continuing into infinity. They create a controlled chaos that has a powerful aesthetic impact, revealing itself as a solution that pacifies the disorder of the reality surrounding us.

The female face, the true protagonist of the mural, captures viewers’ attention and transports them into their own vibrant dimension, pulsing with flashes of light and dynamic energy, perfectly balanced against the coloured lines that traverse the surface.

How to visit the Museum of Time

The Museum of Time can be visited by appointment from Monday to Friday..

Here, you can discover the history of our brand and take a closer look at archive documents, personal accounts, rare examples of industrial archaeology and the awards we have won, as well as the extraordinary works of art that artist Duty Gorn has created especially for us.